In this lesson, we will learn:

- To recall the practical use of titration experiments

- How titration applies to redox reactions.

- How to calculate chemical quantities required in redox reactions.

- How to use the Winkler titration method to find the biochemical oxygen demand (BOD).

Notes:

- We learned the basics of a titration with its use in acid-base chemistry in Acid-base-titration.

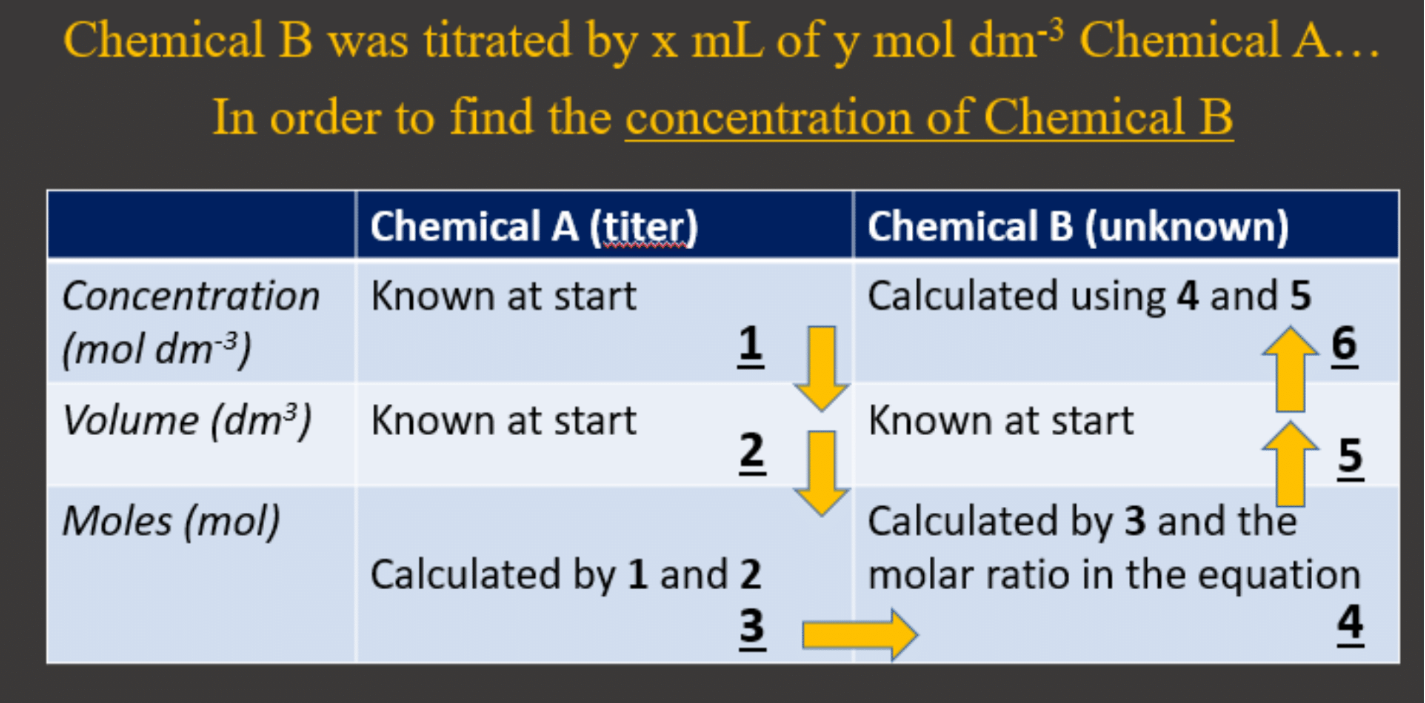

Just like acid-base titrations are used to find the concentration of acids and bases, a redox titration can be done to find the unknown concentration of a chemical in a redox process. The working out and calculations are detailed in Acid-base-titration and is summarized in the image below. Chemical A and chemical B in a redox titration would simply be the two chemicals in the redox (the reducing and oxidizing agent):

- Redox titrations will involve a reducing and oxidizing agent reacting together, but indicator is normally not used like it is in acid-base titrations. This means that one of the reactants used has to be one with a color difference between its reduced and oxidized form. There are two good options:

- Potassium permanganate (KMnO4) is an oxidizing agent that is purple in solution, but turns colorless when reduced to Mn2+ ions.

- Potassium iodide (KI) in solution gives I- ions that get oxidized (lots of chemicals can be used for this part) into brown-colored I2 in solution. Then in a redox titration, I2 can be reduced back to colorless I- ions. Starch can be added (it acts like an indicator for I2) to this, which is blue-black when I2 is present, the color fading when I2 becomes I- again.

- WORKED EXAMPLE:

A solution containing Co2+ ions of unknown concentration is made. 25mL of this Co2+ solution was measured and was titrated by 0.2M MnO4- solution until equivalence point was reached. 19.40 mL of the MnO4- solution was required.

The first thing that needs doing is the finding out of the two half-reactions:- Manganese in MnO4- will be reduced to Mn2+ ions as shown in the half-equation:

MnO4- + 8H+ + 5e-→Mn2+ + 4H2O - Co2+ ions can be oxidized to Co3+ according to the half-equation:

Co2+→Co3+ + e-

The method for working out half-equations in redox was covered in Half equations.

Next, the combining of the two half-reactions will give us the overall equation1 x [ MnO4- + 8H+ + 5e-→Mn2+ + 4H2O ] 5 x [ Co2+→Co3+ + e- ]

These balance for electrons and give the overall equation:MnO4- + 8H+ + 5Co2+→Mn2+ + 4H2O + 5Co3+

This reaction has the cobalt solution as the unknown, so MnO4- with known concentration is being added by burette. MnO4- is purple and as it is added to the cobalt solution, the purple color will disappear as Co2+ reacts it away. When equivalence point is reached the purple color will no longer be removed as there will be no more Co2+ to remove the MnO4- and the purple color that it causes. Therefore the equivalence point is shown by the appearance of the purple color of the MnO4- thats now in excess.

The number of moles of MnO4- can be calculated using the information in the question:Mol MnO4- = 19.40 mL * = 3.88 * 10-3 mol MnO4-

Looking at the equation, we can see a 1:5 MnO4- to Co2+ ratio. The equivalence point will have five times as many moles of cobalt as manganese, then.Mol Co2+ = 3.88 * 10-3 MnO4- * = 0.0194 mol Co2+

With the moles of Co2+ ions now found in 25 mL volume of the sample used, we can calculate the concentration.[Co2+] = = 0.776 M Co2+ - Manganese in MnO4- will be reduced to Mn2+ ions as shown in the half-equation:

- The Winkler method (or Winkler titration) is a way of finding the concentration of oxygen in water systems using a redox titration reaction. This is important for knowing the biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) of a water system, which is a good indicator of water purity. A lot of decaying matter like dead organisms and sewage in the water will cause an upsurge in bacteria, which demand oxygen in their respiratory processes.

The Winkler method makes oxygen the limiting reagent in a redox titration process.

A common redox reaction to do this with is the titration of iodine by thiosulfate ions. The limited supply of oxygen initially oxidises iodide to produce the iodine: - Worked example: Using the Winkler method of titration to find BOD.

- There is a 1:2 ratio of iodine to thiosulfate, so

- There is a 1:1 ratio with iodine and MnO2, which itself is in a 2:1 ratio with O2. So we need to cut this amount in half again:

- This second step needs us to find quantities in grams per decimeter cube. We are currently in moles, so we need to convert to grams and divide by volume in dm3 (where 1 dm3 = 1 L)

The iodine then reacts with the thiosulfate:

The amount of iodine that reacts in the final step is entirely dependent on how much oxygen was available to turn it from iodide into iodine. This is what the Winkler method is trying to find out.

The concentration of oxygen is an indicator of how much is available and not being used up by microorganisms in the water. At any temperature, there is a general solubility of oxygen in water.

With a typical atmosphere of 21% O2 gas, O2 solubility at 298K and 100 kPa (room temperature and pressure) is around 8.2*10-3 g dm-3. Any gap between this value and oxygen concentration in your sample indicates the biochemical oxygen demand (BOD).

A 750 mL sample of water from a lake is saturated with oxygen and left for a week. Afterward, the titration of iodine by thiosulfate ions is run, with the iodine being prepared in solution by reacting with oxygen in the following complete reaction scheme:

5.7 mL of a 0.05 M thiosulfate (S2O32-) solution completely reacted the I2 present in the water sample.

Calculate how many moles of O2 were present in the water. Assuming 8.2*10-3 g dm-3 solubility of oxygen in this water, determine the BOD of this water sample.

This question needs to be answered like a regular titration question first. We need to know how much oxygen is there. We can get this information by the amounts of thiosulfate and the molar ratios involved.

You could say overall there is a 4 : 1 thiosulfate : O2 ratio in this reaction sequence, so cutting the thiosulfate moles by 4 will give us moles of O2.

This is the amount found in a 750 mL sample. This is 3/4 of a litre (or dm3), so this value needs to be divided by 0.75 to find the value for 1 dm-3.

This concentration is the amount of oxygen still available in the water sample. Assuming from above that a saturated sample at room temperature and pressure has a solubility of 8.2 × 10-3 g dm-3, the gap between our concentration and this concentration is the biochemical oxygen demand (BOD):

This is the concentration of oxygen being used up by (micro)organisms in the water system, assuming the level is at equilibrium now.