- To understand energy level diagrams of electron shells.

- How to construct energy level diagrams using electron subshells.

- How to write electron configurations using electron subshell notation.

- How to write electron configurations using noble gas or 'core' notation.

- How an element’s electron configuration relates to its chemical properties.

Notes:

- In Electronic Configuration 1 a basic electron structure was introduced with the 2-8-8 rule. This is useful only for the first 3 rows of the periodic table before the transition metals and it doesn’t look at electron subshells which we need for later elements.

- Evidence that electrons exist in quantum shells comes from the results of atomic emission spectroscopy (AES). When energized, samples of elements like atomic hydrogen give off photons of a fixed wavelength – we call these its spectral lines and they act like a fingerprint for the element. These specific photon wavelengths and energies are evidence that the electrons shifted directly from a state of one specific (quantized) amount of energy to another state of specific quantized energy, which is why they are called quantum shells or energy levels.

Ionization energies (see Periodicity: Ionization energies) are also evidence of quantum levels because of the distinct gaps in energy required at regular intervals as you progress through the periodic table in order of atomic number. For now it is ok, but try to replace ‘shell’ with ‘energy level’ when talking about where electrons are. We will learn why later. - Each energy level (shell) is comprised of orbitals (subshells). We cover orbitals in detail in Introduction to atomic orbitals and energy levels, but you can think of them as shells within a shell or energy level. An orbital is a region of space which can hold up to two electrons each, and there are a few types of orbitals:

- For the first energy level (), one s-orbital exists which contains up to 2 electrons. S-orbitals are spherical shaped; think “s for sphere”. Helium, which has two electrons and therefore a full first energy level, has the electron configuration “1s2”.

- In the second energy level (), three p-orbitals also exist, which can contain up to 6 electrons. P-orbitals are lobe shaped; each p-orbital is two lobes running along an axis in the opposite direction.

With three p-orbitals and one s-orbital, the second energy level holds a total of 8 electrons, so an atom with full first and second energy levels would have the electron configuration “1s2 2s2 2p6”. - In the third energy level (), five d-orbitals also exist which can contain up to 10 electrons. This gives the third energy level a total of 18 electrons.

An atom with completed first, second and third energy levels would have the electron configuration “1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3d10 3p6”. - There is also a fourth energy level that contains f-orbitals which is beyond the scope of chemistry courses at this level.

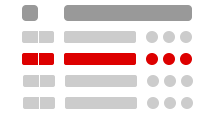

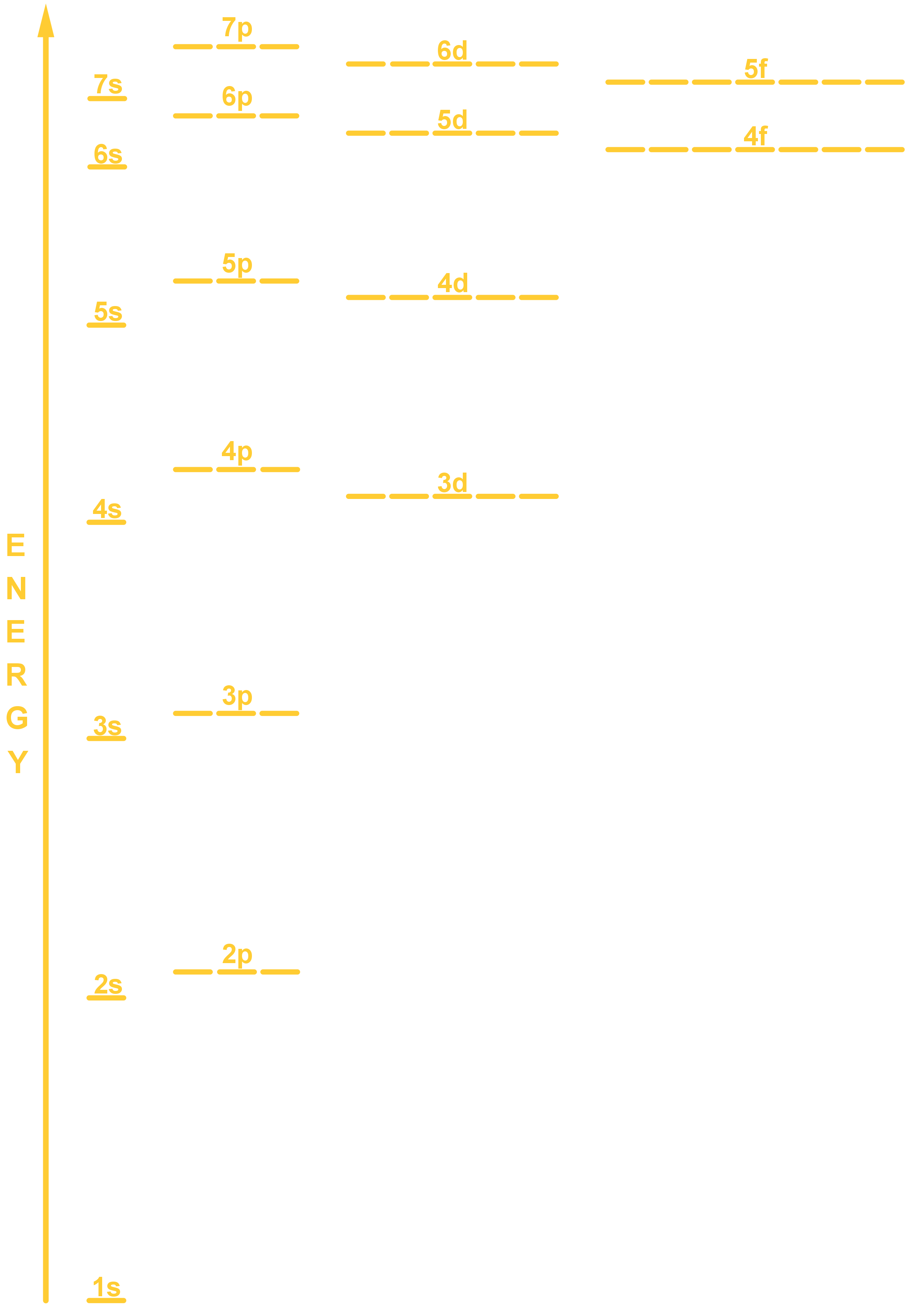

- Orbitals fill with electrons in a specific order according to the energy level diagram, shown below.

- While the evidence for quantized shells comes largely from AES, the evidence for electron subshells largely comes from photoelectron spectroscopy (PES).

- PES is an analytical tool where photons bombard electrons in an elemental sample and the kinetic energy of the electrons ejected is found. By knowing the energy of the photons used () and measuring the ejected electrons’ kinetic energy, we can work out the binding energy of electrons to the atoms when they were in the sample. This is how much energy it took to ‘kick out’ the electrons from whatever state they were in.

- In any given elemental sample, the electrons’ binding energy show distinct gaps. This supports the idea of quantized electron energy levels with fixed energy gaps between them.

But where the binding energies appear, there are often groups of different binding energies. These are the s, p, d subshells or ‘shells within shells’ better known as orbitals. - Electron configurations in an atom can be shown in three ways.

- You can use an energy level diagram, just by filling in the labelled orbitals (represented as lines) from lowest energy to highest. The energy level diagram is shown below. It reflects a few pieces of important information that is essential to writing electron configurations correctly:

- An s-orbital (say, 3s) is lower energy than a same level p-orbital (3p), which is lower energy than a d-orbital (3d).

- Electrons always fill lower energy subshells before higher energy subshells. For example, 2s will always fill before 2p. The energy-level diagram shown above has the correct order of subshells.

- Electrons must fill orbitals singly first and only pair up after this. They must pair up with ‘opposite spin’; one pointing up, one pointing down.

- The gaps between increasing energy levels gets increasingly small, which is why 3d is higher energy and fills up after 4s, which is why it is the 2-8-8 rule and not 2-8-18!

- Up to including the f-orbitals, the shells fill with the following number of electrons: 2 (1s); 8 (2s, 2p); 8 (3s, 3p); 18 (4s, 3d, 4p); 18 (5s, 4d, 5p); 32 (6s, 4f, 5d, 6p).

- You can also show electron configuration by writing in subshell notation.

- Subshell notation does not require drawing an energy level diagram. It is written in the format nxy where is the energy level, is the subshell and is the number of electrons in that subshell. For example: 2p4 would mean there are four electrons in the 2nd level p-subshell.

- Like the energy-level diagram, the lowest energy subshells is written first. For example, the electron configuration for carbon is written: 1s2, 2s2 2p2.

- There is another way to write electron configuration, known as noble gas notation or core notation.

- This uses the chemical symbols of noble gases in square brackets, and only writes the subshells for the highest incomplete energy level. Noble gas symbols are used because their electron configuration are full shells; it is writing a shorthand.

- For example: [Ar] has the configuration (2,8,8) so the configuration of K could be written: [Ar] 4s1. Other than this shortcut, core notation is very similar to regular subshell notation.

- To write the configuration for ions, see whether the ion is negative (it has gained an electron) or positive (it has lost an electron) and add or remove electrons as needed. If a subshell was the last to fill up, it is the first to empty! The only exception to this is with the 3d subshell.

- The highest (partially) filled subshell for an element is how we say what “block” an element is in.

- For example, lithium’s electron configuration of 1s2 2s1 shows its highest energy electron in an s-orbital, so it is an s-block element.

- Likewise, boron is called a p-block element because its configuration of 1s2 2s2 2p1 shows its highest energy electron in a p-orbital.