Properties of Determinants

Determinant definition

Although we have already seen lessons on how to obtain determinants such as the determinant of a 2x2 matrix and the determinant of a 3x3 matrix, we have not taken a moment to define what a matrix determinant is on itself. Therefore, this lesson will be dedicated to that, to learn the significance of matrix determinants and their properties, rules and even some of its applications.

A determinant is a scaling factor for the array of numbers found in a matrix which can give us information about these values as components of a vector system or a linear equation system. The first thing to remember when working through these linear algebra operations is that we can only calculate determinants of squared matrices, which are those with the same amount of rows and columns (thus the "squared" name, since their width is the same as their length in terms of quantities of rows and columns), and so, a determinant is that informative factor that comes from a system of equations containing the same amount of unknowns as vectors, which then can be solved to find the value of each unknown. Thanks to the determinant we can also calculate a matrix inverse.

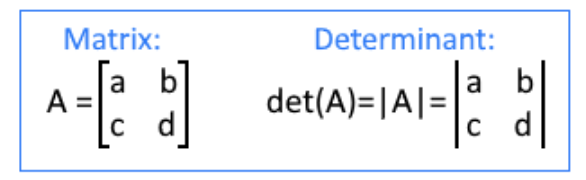

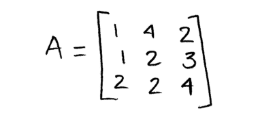

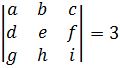

The determinant of a matrix can be denoted simply as det A, det(A) or |A|. This last notation comes from the notation we directly apply to the matrix we are obtaining the determinant of. In other words, we usually write down matrices and their determinants in a very similar way:

But notice, when we write down the matrix we have two brackets that are closed inwards, and when we are referring to the determinant of the matrix, the matrix components are surrounded by two straight lines.

When the determinant of a square matrix is zero, we call this a singular matrix. Recalling from lessons on the inverse of a 2 x 2 matrix and the inverse of 3 x 3 matrices with matrix row operations, we know that the operation of inverting a matrix happens to be the reciprocal of the matrix and thus, you can only obtain the inverse a matrix if the result multiplied by the original matrix produces the identity matrix. How is this important when talking about singular matrices? Well, in order to obtain the inverse of a matrix the general process requires you to obtain the determinant of the original matrix, swapping the positions of the values in the original and dividing this new matrix by the determinant gotten. Therefore, for a singular matrix this would mean to divide by zero, which cannot be done, and so, singular matrices are not invertible.

Whenever you obtain a zero value as the result of a determinant, remember this matrix cannot be inverted. This note can simplify the process of certain problems you may need to solve in the future.

How to find the determinant of a matrix

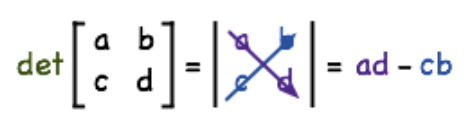

As seen in past lessons, we obtain the determinant of a squared matrix through a simple general method. For the determinant of a 2x2 matrix we follow the process shown in the equation below:

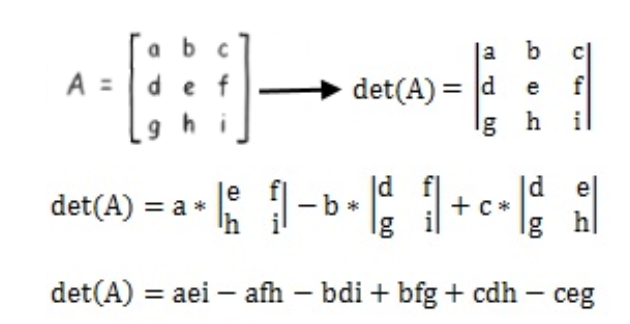

The same general method, with a slight variation, can be used to obtain the determinant of a 3x3 matrix:

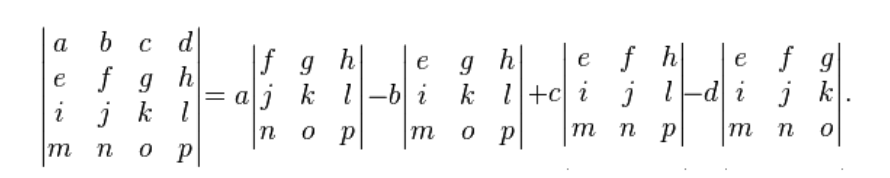

If you think you need a little bit more of practice solving determinants, please make sure to visit the two lessons referred above on the very first paragraph which explain how to solve a 2x2 and 3x3 operation. The determinant of a 4x4 matrix is solved similarly than the 3x3 through the general method of decomposing into a smaller square matrix and follow a process already known. For reference we have included the next rule on how to solve the 4x4 matrix determinant, but we will not be using it much through this lesson since these kind of operations tend to get lengthy as you can see:

Now that we have seen what a determinant is and how to calculate it, let us focus on the main topic for this lesson: the properties of matrix determinants and some of their applications. In the next section you will see a combination of the definitions of the basic properties of determinants and then an example in each case. In some cases we will add applications to such problems.

Matrix determinant properties

There are a lot of properties of determinants but today we will focus on the main ones which will allow you to go through linear algebra problems swiftly. We have divided such properties in the next three subcategories, each of them containing a few rules.

- Row operation properties

Having A being a nxn matrix (a square matrix). Then:

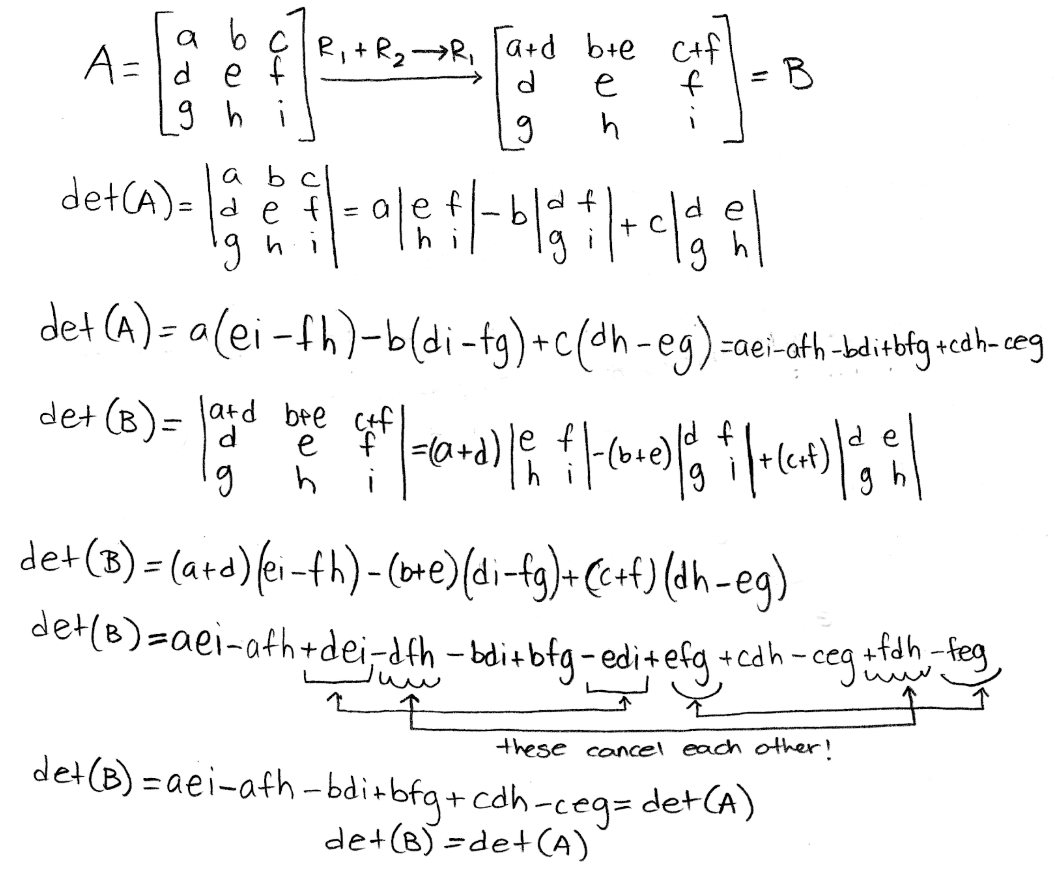

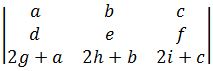

- If a multiple of one row of matrix A is added to another row to produce matrix B, then det(B) = det(A). This rule can be explicitly explain below:

Equation 5: Explicit explanation for row operation property 1 Looking at an example with a determinant of 3x3 matrix:

Equation 6: Example for row operation property 1 As you can see, this simple rule is used in the row-reduction method. In truth, all the row operation properties are useful while doing row-reduction of a matrix. Just remember that some operations can change the value of the determinant of the matrix, as you will see in the next ones.

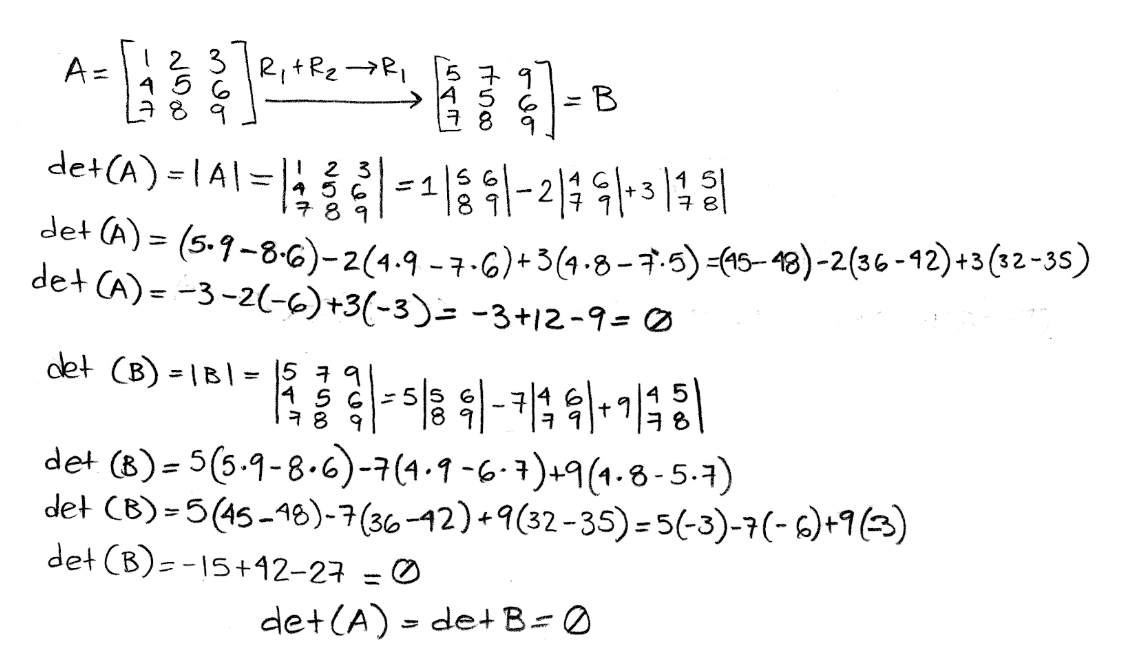

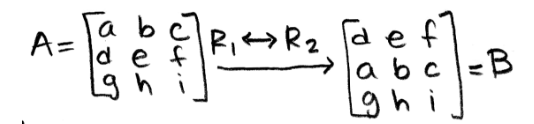

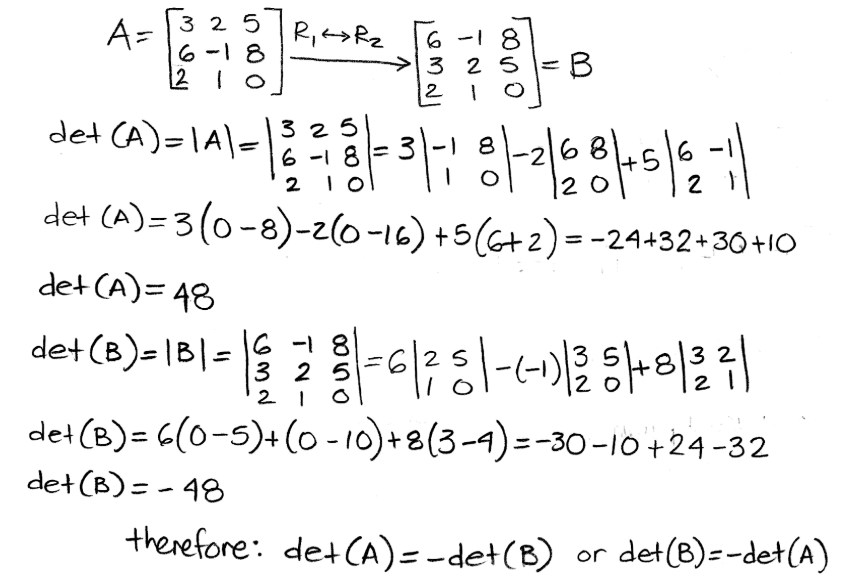

- If two rows of A are interchanged to produce matrix B, then det(B) = -det(A).

This is because changing the order of the values found in in the matrix will produce a different way how they are operated during the determinant. Take a look at the explicit explanation of this process:

Having matrix A and swapping two rows to produce matrix B

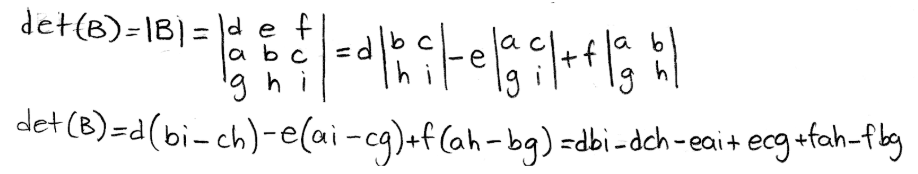

Equation 7: Matrix A and B produced by switching rows We know from property 1 that the determinant of matrix A is det(A)= aei-afh-bdi+bfg+cdh-ceg (you can check this in equation 5, since we are using the same matrix A for the explicit explanations). So we only take the time to obtain the determinant of B in this case:

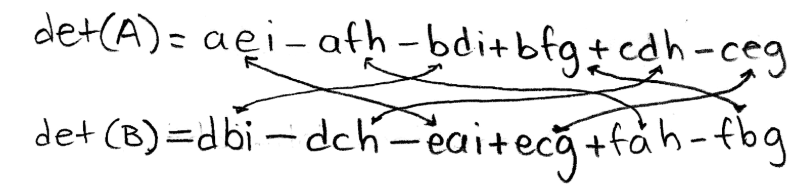

Equation 8: Determinant of matrix B Next, we compare det(A) with det(B) by checking for equal terms. Remember that when multiplying variables and regular numbers, the order of the factors does not alter the product.

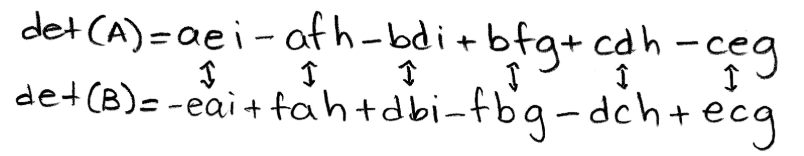

Equation 9: Comparing the determinants of A and B Rearranging the terms in det(B):

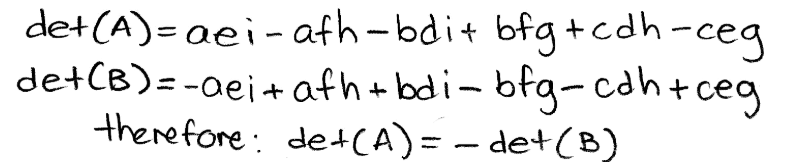

Equation 10: Rearranging terms in det(B) And now we rearrange the order of the variables on each term on det(B) to finally see how det(A) and det(B) are related:

Equation 11: determinant of A is equal to the negative determinant of B Let us now look at an example with a 3x3 determinant:

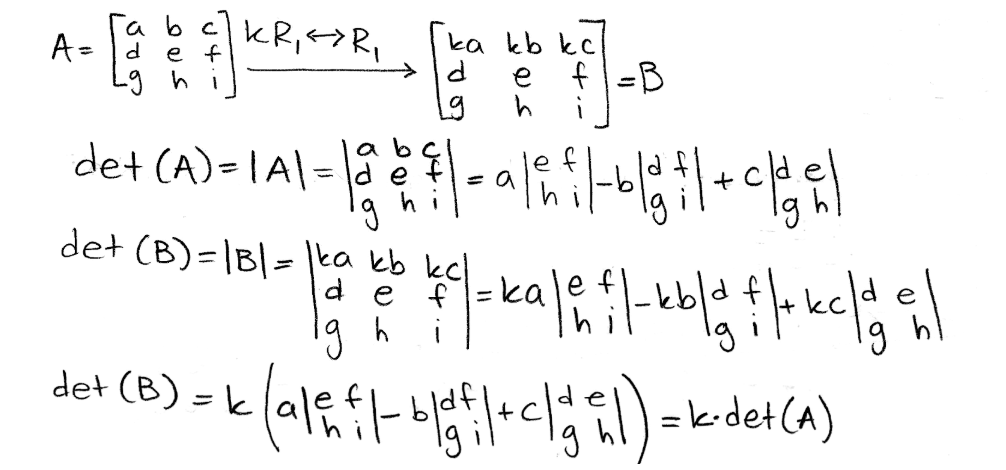

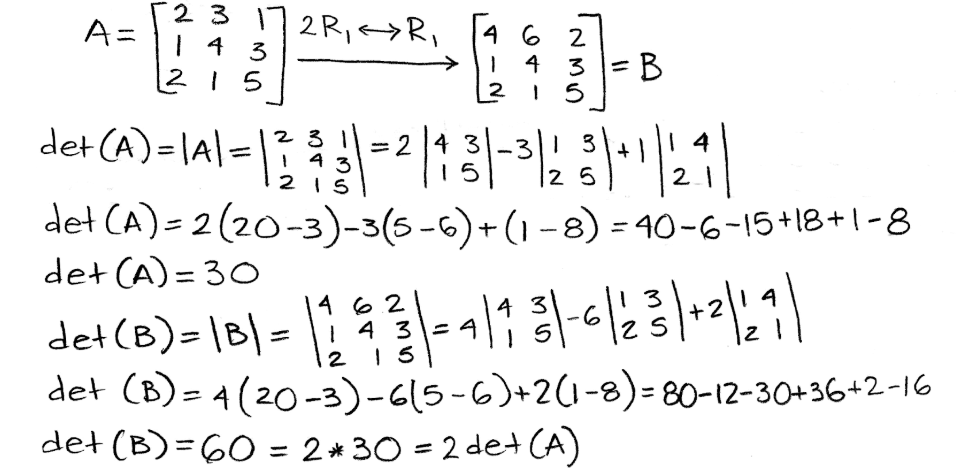

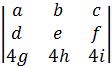

Equation 12: Example of property for swapping rows in matrices - If one row of A is multiplied by k (k being a constant value) to produce matrix B, then det(B) = k*det(A).

This particular property is very simple to understand. The best explicit explanation comes from multiplying the first row of the matrix by a constant value, since in this case it can be directly observed how the constant factor gets spread around the whole determinant of the matrix and thus, the process retains the proportionality of the operation producing a proportional result at the same scale as the factor introduced. Looking at it mathematically:

Equation 13: Explanation for the result of a multiplication of a coefficient in a matrix and the resulting determinant Observing this effect on the determinant of matrix A, where A is the following 3x3 matrix:

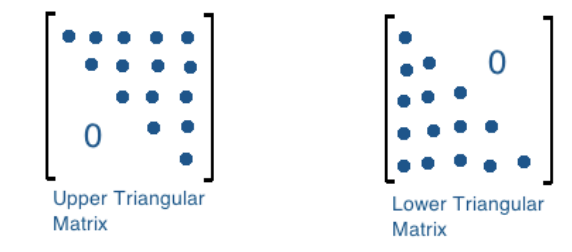

Equation 14: Example for row operation property 3 - For triangular matrices, the product of the diagonal entries equals the determinant.

An upper triangular matrix is a square matrix in row echelon form in which all of the pivots are in consecutive columns producing the main diagonal, thus resulting in a triangle made out of zeros below the main diagonal. One can also have a lower triangular matrix, which is the one where the zeros are found above the main diagonal, but we will only use the upper triangular matrix form in our lesson since is the one that comes from having a matrix in echelon form.

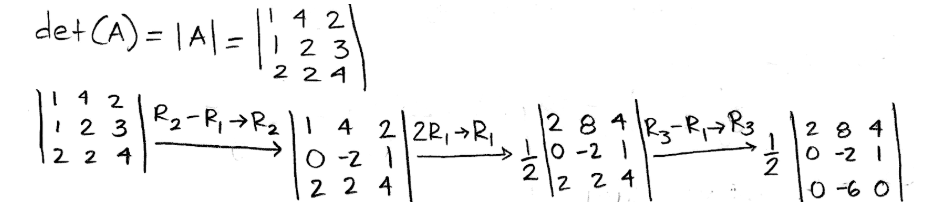

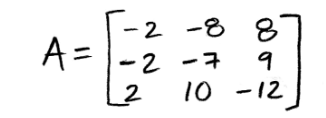

Equation 15 :Upper and lower triangular matrices So how are triangular matrices important for row operation properties of matrix determinants? They matter because we can use the row properties we saw before to row reduce a matrix to echelon form and find its determinant. Therefore, upper triangular matrices provide us with another method of solving a matrix determinant which is much simpler! Let us take a look at the example below where we will find the determinant of matrix A:

Equation 16: Matrix A Row reducing its determinant:

Equation 17: Row reduction of det(A) part 1 Notice how in the first row operation the determinant value does not get affected due to property 1, which says that adding or subtracting rows do not change the determinant. A different case happens during the second row operation due to property 3. Since the first row is being multiplied by a constant, the value of the determinant is multiplied by that constant too (in this case multiplied by 2), and thus, a factor of one half has to be put in place to keep the value of the original determinant. During the third operation, the value of the determinants continues constant since property 1 is being applied again.

The determinant is not in echelon form yet, and so, we continue with the row-reduction:

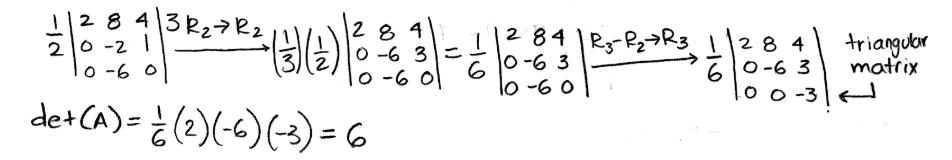

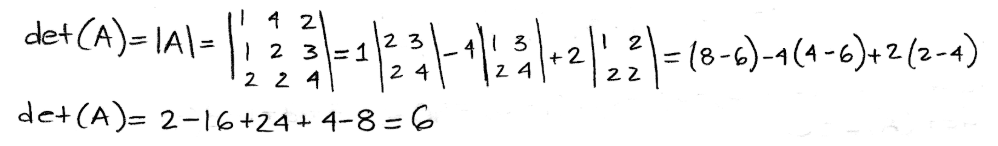

Equation 18: Row reduction of det(A) part 2 and result for the determinant. Pay attention to all the factors outside the determinant, which are to compensate the multiplication of a constant value to certain rows through the process. We can show the proof of this particular method by obtaining the determinant of matrix A once more, but now following the general method:

Equation 19: Determinant of A through general method Since the method of row reducing a determinant into an upper triangular matrix can be a little confusing, more so because you may need to use all of the row operation rules of determinants during the row reduction part, let us work through a second example of it for a little more practice.

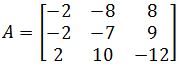

And so, compute det(A) by row reduction to echelon form, where the matrix A is:

Equation 20: Matrix A for row reduction method into triangular matrix We now row reduce the matrix into its echelon form to obtain an upper triangular matrix and so, obtain its determinant by multiplying the values of its main diagonal.

Equation 21: Determinant of an upper triangular matrix

- If a multiple of one row of matrix A is added to another row to produce matrix B, then det(B) = det(A). This rule can be explicitly explain below:

- Multiplicative properties / other properties

There are more properties of matrices and determinants than the ones seen above for row operations, in this case we take a look at determinant multiplication rules, which tend to be quite useful when reducing the amount of work for solving a problem.

Letting A be a nxn square matrix, we have the next three multiplicative determinant properties:

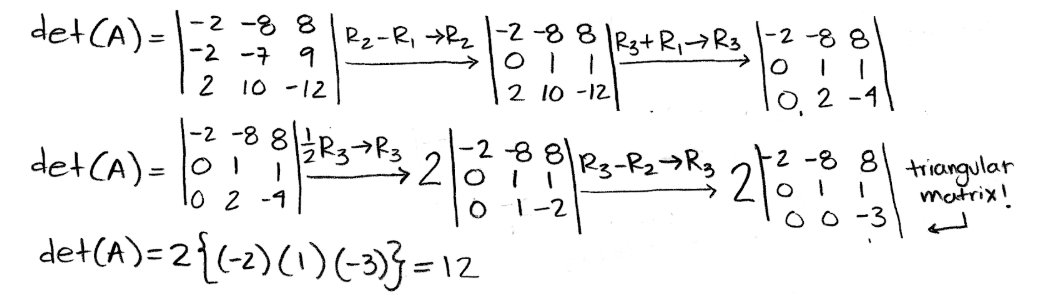

- det(A) = det ( det (A) = det ()

This means that if we have a given matrix A, its determinant is the same as the determinant of the transpose matrix of A. Remember, the transpose of a matrix means that when having an original given matrix, you take all of its columns and rearrange them as rows to form a new matrix which is the transpose of the original.

So, let us go through a simple example of this where we will have an original matrix A, obtain its transpose, and then obtain the determinant of both matrices to compare them:

Equation 22: det(A) = det(A-transpose) Therefore, as long as you have an square matrix, you can obtain its transpose and the determinant of the original matrix will be the same as the determinant of the transpose matrix. Here is another simple example before we continue onto the next multiplicative property:

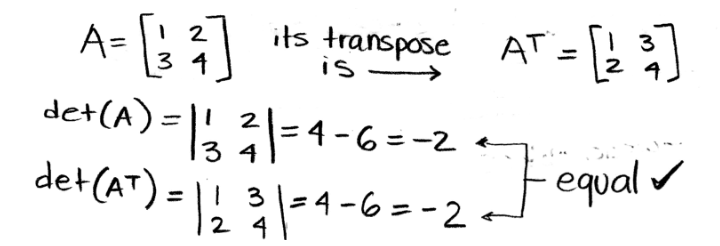

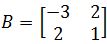

For this case you are given the two matrices A and B:

Equation 23: Matrix A and Matrix B Calculating their determinants to show they are equal to the matrices' transposes:

Equation 24: Determinant of a matrix equal to the determinant of its transpose - A is invertible if and only if det(A) is different to zero.

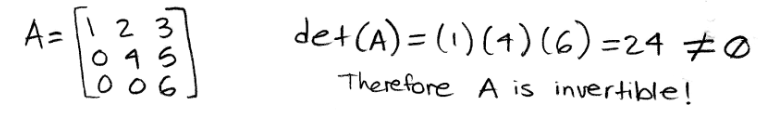

We have already talked about this in the first section when mentioning singular matrices. In other words, this property says that as long as your square matrix is nonsingular, you can invert it. Let us look at the example below where the question is, is A invertible?

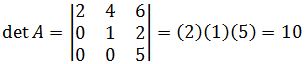

Equation 25: A is an invertible matrix This case is wonderfully simple because A is an upper triangular matrix, a square matrix in echelon form with all zeros below the main diagonal. Therefore, we can use the fourth property for row operations which says that the determinant of this kind of matrices is equal to the multiplication of the values found in the main diagonal.

Again remember that matrices which have a determinant equal to zero cannot be inverted, because the matrix inversion process requires you to divide by the determinant of the original matrix. This would then result in a division by zero which is undefined and so, this rule happens to be pretty straight forward.

- det (AB) = det(A) x det(B)

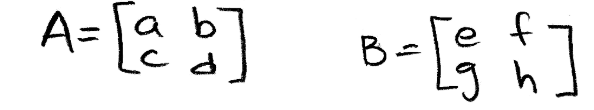

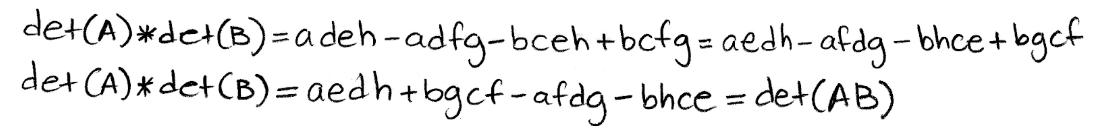

This multiplicative property is pretty straight forward too, it just means that when you have two matrices, the multiplication of their determinants is the same as the determinant of the matrix multiplication. Let us prove this explicitly having two matrices A and B as follows:

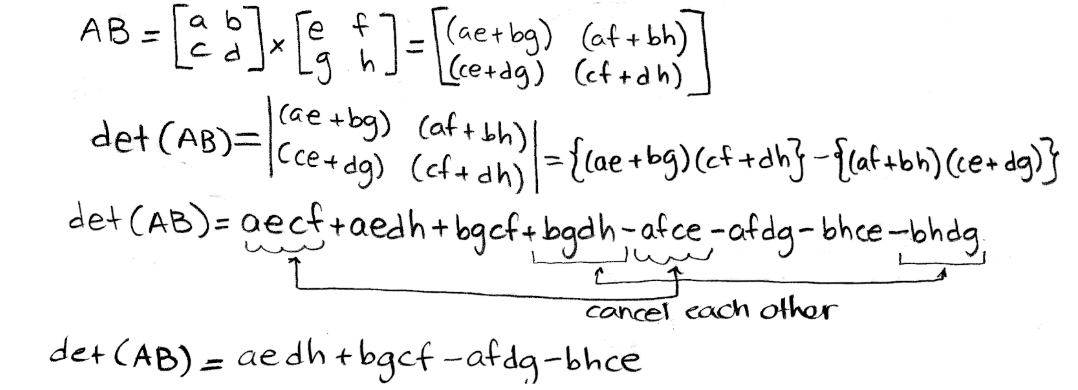

Equation 26: Matrix A and matrix B Start by working up the left hand side of the property equation:

Equation 27: Determinant of AB Now for the right hand side:

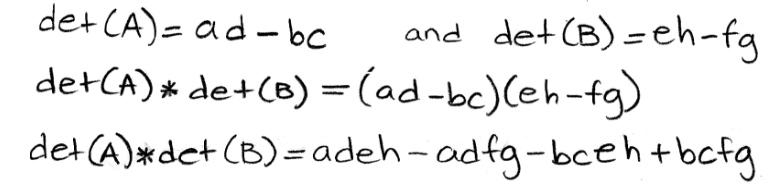

Equation 28: Multiplication of the determinants of A and B Rearranging the terms, and the order of the variables in each term of the result for the right hand side, we can compare the results for both sides directly now:

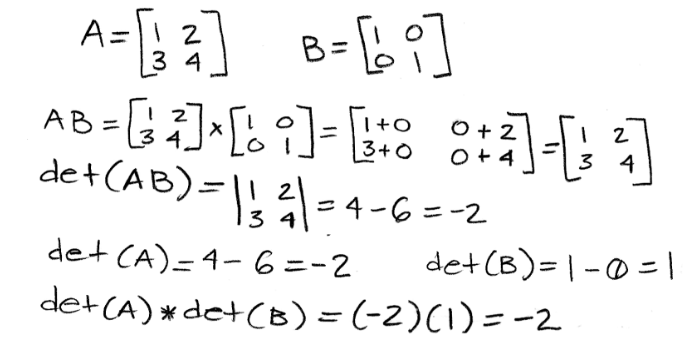

Equation 29: Proof of multiplicative property 3 Proving the same property using matrices with given values:

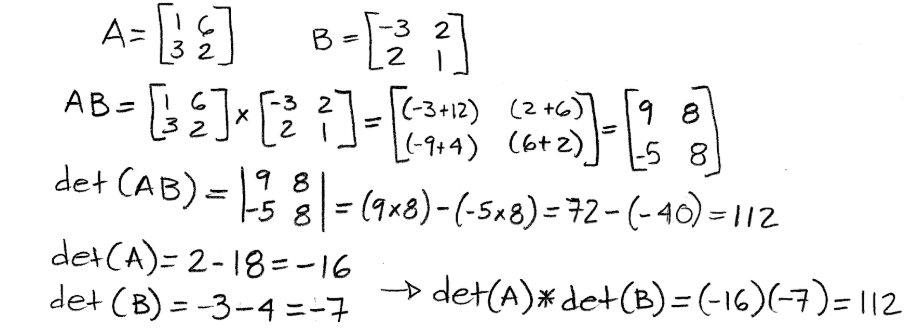

Equation 30: Example of proof for multiplicative property 3 Once more prove that det (AB) = det(A) x det(B) with the next two matrices:

Equation 31: Example of proof for multiplicative property 3

- det(A) = det ( det (A) = det ()

- Applications to determinants

After looking at the properties of a determinant, is time to look at two important applications of these properties and the determinants themselves:

- if det(A) is different to zero, then the columns of the matrix A are linearly independent.

- if det(A) is equal to zero, then the columns of the matrix A are linearly dependent.

In other words, just by looking at the determinant of a square matrix we can know if the column vectors composing the linear system of equations for this matrix are either linearly independent or not. When the determinant is equal to zero, the vectors are linearly dependent, when the determinant is any other value different than zero, then the column vectors are linearly independent.

Example:

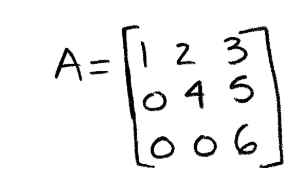

Equation 32: Upper triangular matrix A Using our knowledge on triangular matrices, we know the determinant of matrix A can be obtained just by multiplying the values on its main diagonal. Therefore det(A)=(1)(4)(6)=24. This determinant is different than zero, and thus the column vectors belonging to matrix A are linearly independent:

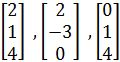

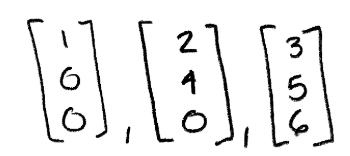

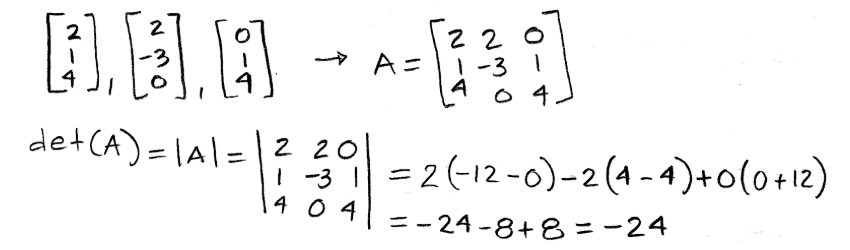

Equation 33: Linearly independent column vectors Now let us use determinants to decide if the set of vectors below are linearly independent:

Equation 34: Proving a set of column vectors is linearly independent The determinant is different to zero, therefore, the vectors in the given set are linearly independent.

To finish off this lesson, there a few link recommendations we would like to give in case you want to continue your studies on this topic and see many more examples. First of all, here is a lesson on determinants that gives a summarized set of properties and ends with several examples. Next, there is this article on the properties of determinants of matrices which provides mnemonic devices to remember the different rules, which you may find useful. And last but not least, this particular section on properties of determinants gives another approach to all of the rules explained throughout this lesson.

We hope you enjoyed this lesson and see you in the next one!

1) If a multiple of one row of matrix is added to another row to produce matrix , then det det

2) If two rows of are interchanged to produce matrix , then det det

3) If one row of is multiplied by to produce matrix , then det det

If is an matrix, then det det

A square matrix is invertible if and only if det .

The Multiplicative Property

If and are matrices, then det (det )(det )

It may be useful to know that the determinant of a triangular matrix is the product of the diagonal entries. For example,

.

. ,

,

and

and  .

.