Inner product, length and orthogonality

The time has come for us to work on vectors. As we know, a vector is a mathematical object with a magnitude and a direction. We know how to represent vectors geometrically in coordinate systems, and we know how to make a few calculations with them, let look at one of its main characteristics (length) and then continue with one of the operations that can be performed with them: the inner product.

The length of a vector The length of a vector, which is also called its norm refers simply to the magnitude of the vector. So, what is that in simple words? Just as the word length defines it, the length is just that; for example: if you have a vector you know this is represented geometrically as an arrow, thus its length will be the quantity measured of the distance from where the vector tail starts to its arrow-tip. This is what we call its magnitude, its length or its norm (any of the three words can be used interchangeably, but the standard in mathematics textbooks is usually the word magnitude since it is intuitive to think this quantity gives us the size of a vector).

The formula to calculate the magnitude of a vector goes as follows:

In this case represent the variables of the vector, in other words, if you have a vector in terms of and , then: and , therefore, its magnitude (length) formula would be:

And important identity to remember about the magnitude of a vector is that the multiplication of a vector by itself is equal to the square of the magnitude of the vector:

This makes sense since multiplying a vector by itself means that you will multiply each term in the vector by itself. These multiplications by themselves will always produce positive results, because no matter if a term inside the vector is positive or negative: a positive times a positive produces a positive same as a negative times a negative produces a positive, thus, this is the same as obtaining the magnitude of the vector and just square it.

Talking about magnitudes of vectors, there exist vectors that can have a magnitude of one, those vectors are called unit vectors.

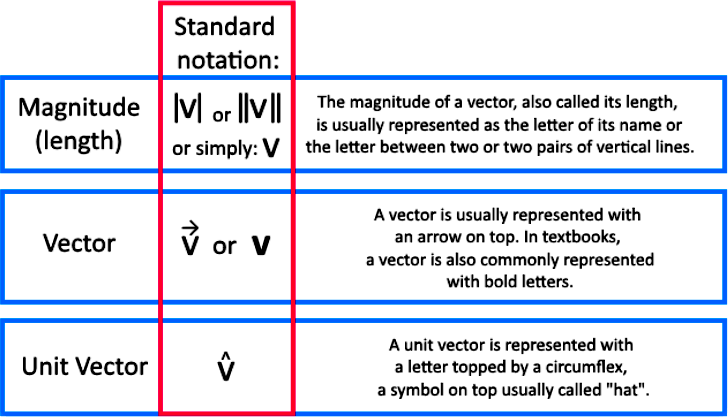

Knowing this, it is important to know the notations used to represent vector magnitudes, vectors and unit vectors. Notice that in equation 1 the magnitude (length or norm) is denoted with the letter coming from the name of the vector enclosed in between of two vertical lines, the magnitude can actually be represented in many different ways. In the next table we show you the most common ways vectors and magnitudes are represented:

And so, we can now understand the formula for a unit vector:

Therefore:

Vector can be written as: or .

The magnitude of vector can be written as: .

And the unit vector v is written as: .

Note that during this lessons problem equations we will usually denote vectors just by their letter name instead of putting an arrow or bold caps (this is due to differences within software symbols and lack of the appropriate symbols in certain tools), for that reason, we will make sure to denote the magnitude of a vector as the letter name enclosed by two vertical lines in order to be able to differentiate them always.

What is inner product?

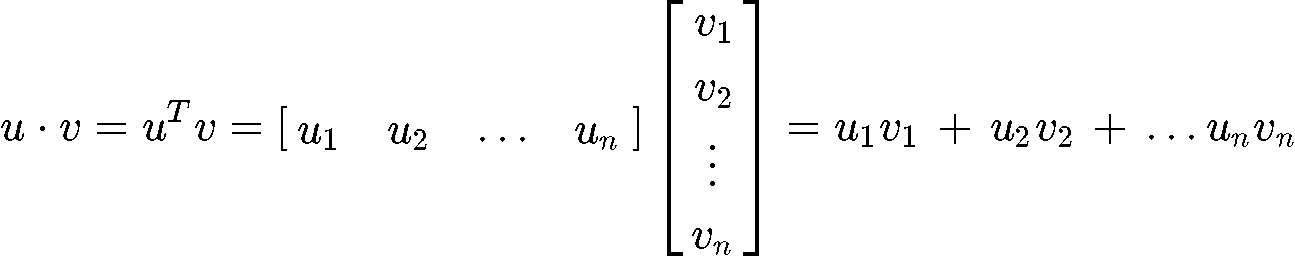

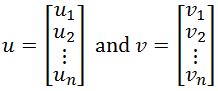

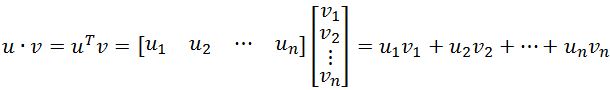

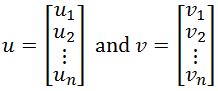

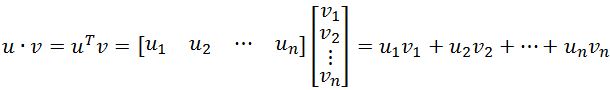

If we think of two column vectors being multiplied as vector spaces, the inner product happens to be the dot product which can be defined as:Where is the transpose of vector and is simply the vector .

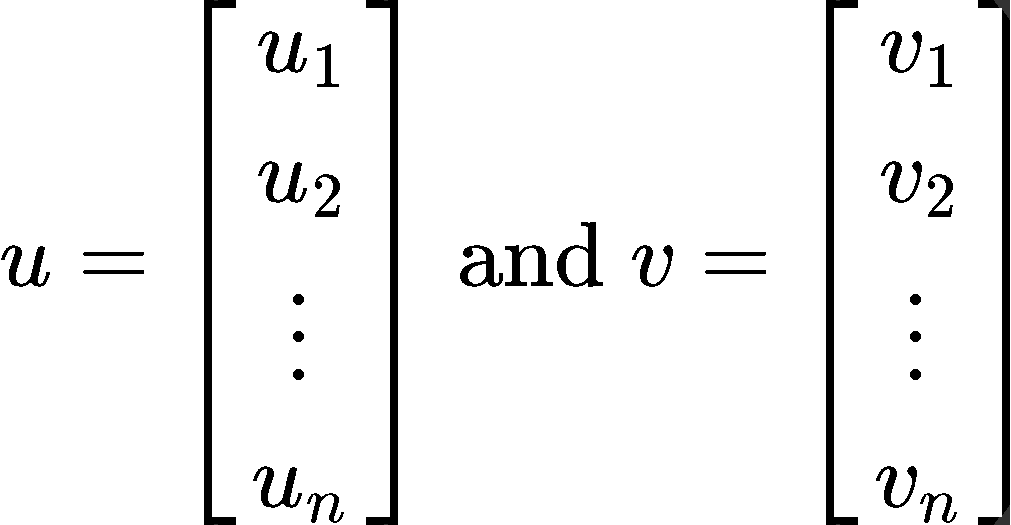

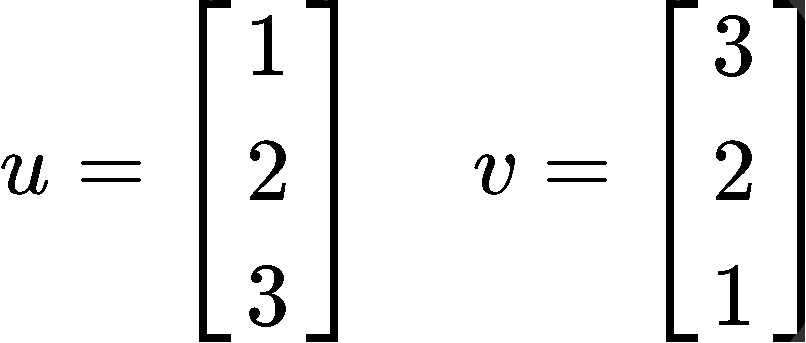

Therefore, if we have the two vectors and defined as follows:

Then the inner product of the two vectors is:

Inner product properties

Just as the square of the magnitude of a vector identity shown in equation 3 is useful, we have a few inner product properties listed below. These properties can be of aid later in the lesson while solving problems.1.

The first property defines that the inner product, or dot product of two vectors is commutative, in other words, you can change the order in which two vectors are being operated on through an inner product and the result will not be affected.

2.

This is what we call the distributive property which allow us to distribute the effect of the outer factor, in this case vector w, to be applied to both of the vectors inside the parentheses without affecting the operation happening in there (the addition). The distributive property works for both, addition and subtraction operations being performed inside of a parenthesis with a factor affecting both elements of the inside operation.

3.

The associative property of the inner product says that when having such multiplication of more than two vectors, it does not matter which ones you associate and multiply first to then use the result of this first operation to multiplicate with the one that it is left. In other words, the associative property allows a longer multiplication containing a bigger quantity of vectors, to be broken down in pieces to be solved by steps without affecting the final result.

4. and only when

This property complements equation 3 by saying the result of the inner product of a vector by itself will always result in a scalar higher than zero (as explained before) unless the vector in itself is zero, which would produce the multiplication of zero times zero, equal zero.

What is dot product

Mathematically speaking, the dot product definition is:The inner product is a generalization which can also be defined as the dot product, or scalar product (due to the result it produces when vectors are being multiplied this way). The dot product formula as seen in equation 8 aids in the definition of orthogonality, which is the quality of two elements such as vectors of being perpendicular to each other.

In this case, we can know if a pair of vectors are perpendicular (or orthogonal) to each other by computing its dot product since: The dot product of perpendicular vectors is equal to zero.

The other way around also helps us in obtaining information from euclidean spaces and vectors, since one can obtain the angle between vectors by using dot product.

Cross product vs dot product

When multiplying vectors there are two different kind of basic multiplications, the dot product and the cross product. The main difference between them is that the result of a vector dot product is a scalar and the result of a cross product is a vector perpendicular to the plane of the two original vectors. We will go deeper into this topic in later lessons, but for now it is important you remember that the result of each operation gives these two multiplications their nicknames: the vector dot product is also called the scalar product, while the cross product is also called the vector product.Example problems

For this section we will work out through various examples where we are to compute (or use) the inner product of two vectors to solve the given problems.

Example 1

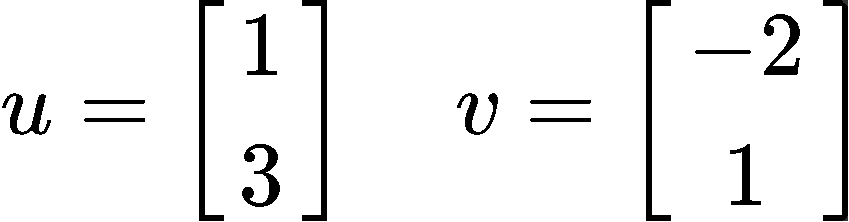

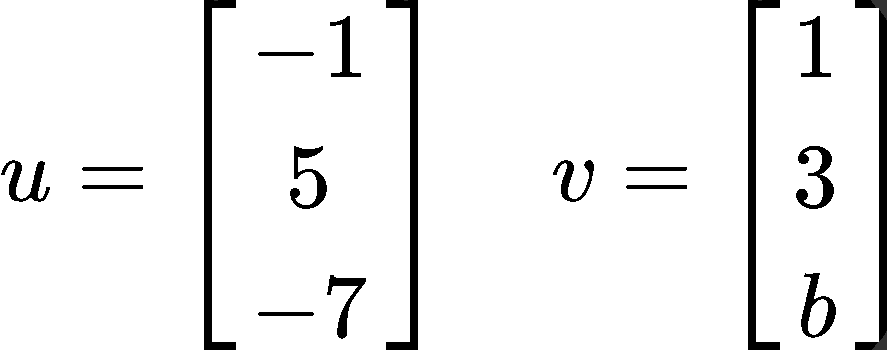

Given the vectors u and v as shown below:

Compute the operation:

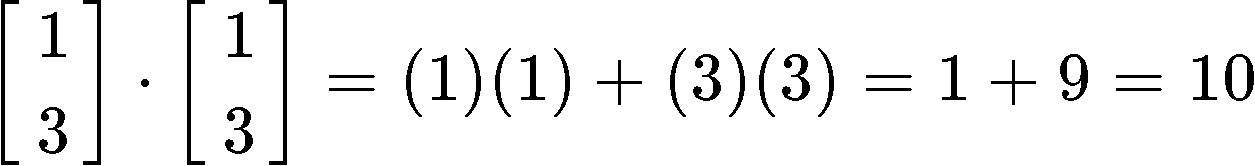

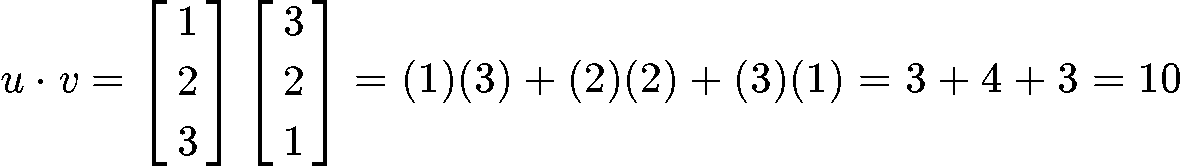

We start by computing the dot product of vector by itself:

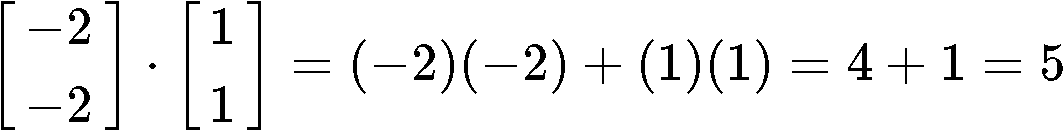

Now computing the dot product of vector by itself:

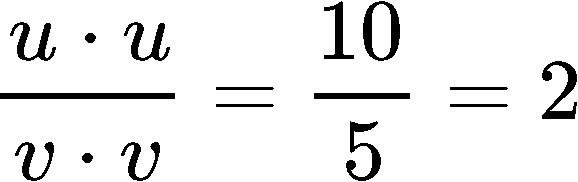

These two resulting numbers allow us to perform the division of the dot products quite easily (note how all of the elements entering this operation were vectors and the result is a scalar, this is why the inner product space is called the scalar product of vectors):

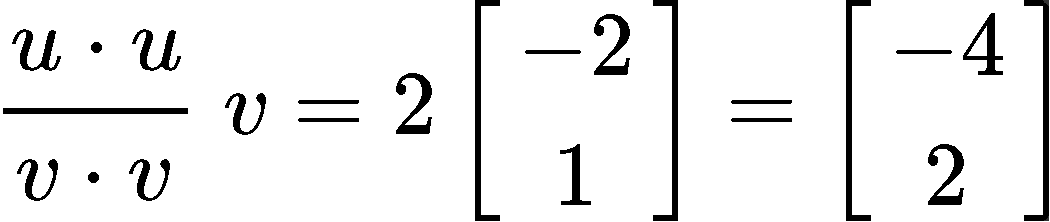

And so, we finish our calculations by multiplying by vector to obtain a final vector as follows:

Example 2

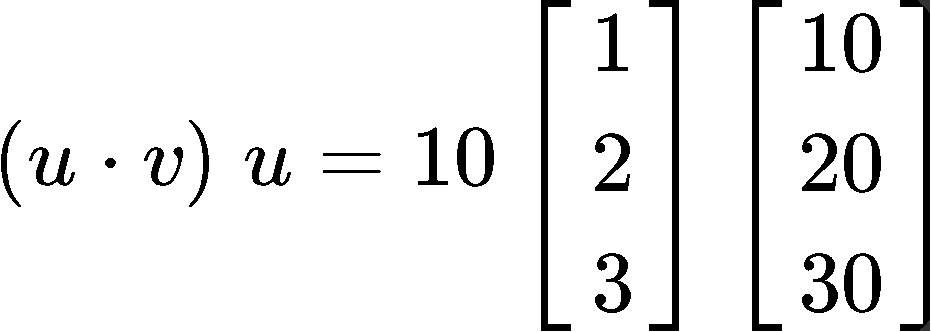

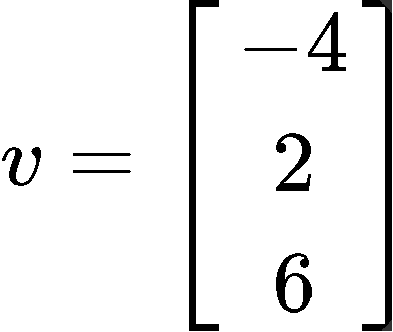

Given the vectors and as shown below:

Compute the operation:

Notice that since the multiplications we are to perform are all surrounded by double vertical lines, it means we are about to obtain a magnitude as a final solution for this operation. We start by computing the dot product of vectors and :

Multiplying this result by vector as asked:

Now we just need to compute the absolute magnitude of this resulting vector in order to obtain our final result:

And so, our final answer is a scalar (which makes sense since we are finding the length of the vector found in equation 16), this scalar is equal to the square root of 1,400. You could finish off and perform the square root on this number, but it is not necessary, to avoid the messiness of a number with decimals we can just keep the answer as it is.

Example 3

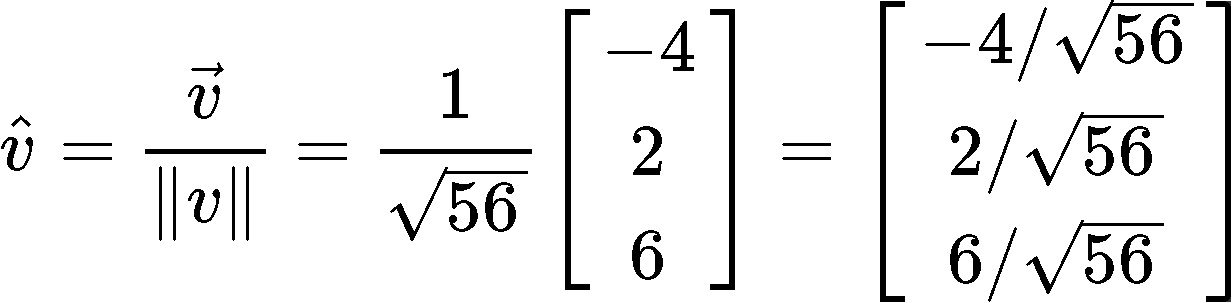

Find the unit vector in the direction of the vector as defined below:

To solve this problem we make use of equation 4, the equation for a unit vector, thus, we have to find the magnitude of vector first:

Given that we don't want to deal with decimal numbers, we leave the result as is with the square root sign, and now we perform the division to find the unit vector :

Example 4

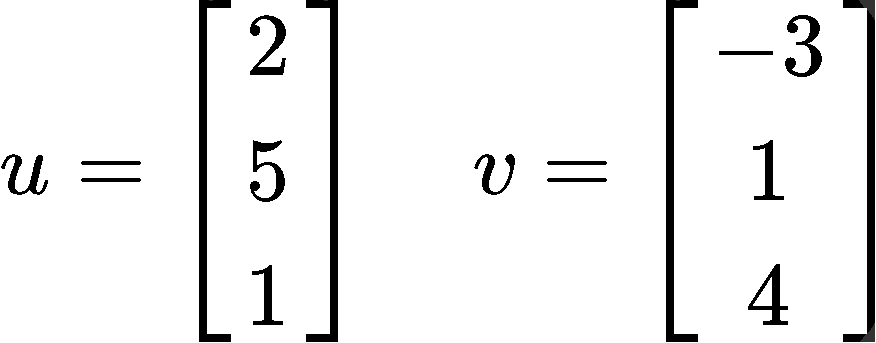

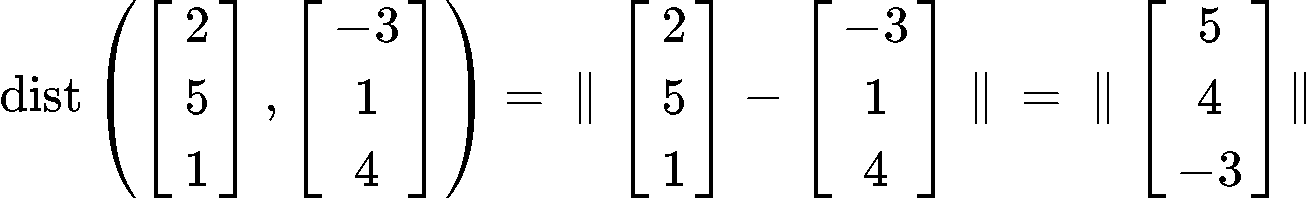

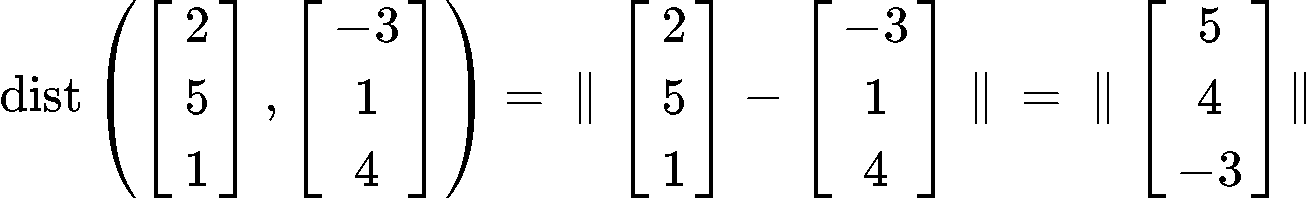

Find the distance between the vectors and as they are defined below:

In order to find the distance between two vectors we must subtract the vectors in question and then obtain the absolute magnitude of the resulting one, in other words, we must obtain the vector that would represent the distance between one and the other, and then the absolute magnitude is computed in order to know the length (in quantity) of such distance.

The process can be summarized in the next operation:

Notice how the equation above can be read as: the distance between vectors u and v is equal to the absolute magnitude of the subtraction of those two vectors, equal to the absolute magnitude of the vector resulting from the subtraction of the two vectors. Then, we perform the magnitude calculation to obtain the final result:

And so, the distance between vectors u and v is equal to the square root of 50.

Remember that subtracting means finding the difference between two quantities, in this case, between the two vectors. Since we will obtain the magnitude of the resulting vector from the subtraction, it does not matter the order in which you perform the subtraction of the vectors for this particular case. This is because the order of a vector subtraction affects the direction of the resulting vector, but it does not affect its magnitude and so, either you perform the subtraction as or will not matter for this case.

You can prove this by performing the operations once more but now using the other order in the vector subtraction, we do encourage you to check it out!.

Example 5

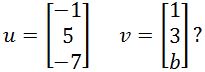

What value(s) of b make vectors u and v orthogonal if they are defined as shown below:

Remember the orthogonality condition says that for two vectors to be orthogonal, their dot product must be zero, thus: .

And so, we can paraphrase the question to: what values of b will produce a dot product of 2 vectors and equal to zero? Well, let us find out!

If we perform the dot product of u and v and set it equal to zero, we can then solve for the b value that will agree with that condition:

And we find that if is equal to 2, then the dot product of and will be zero, and so, they will be orthogonal.

Example 6

Show that the parallelogram is true for vectors and in . In other words, show that:This problem is all about playing with the terms around following the dot product rules, and so, we are to remember the dot product properties before we start:

- → square magnitude identity

- → distributive property

- → commutative property

Knowing this, let us work through the left hand side of equation 26 in order to solve it until we arrive to the result on its right hand side. First we simplify by using the magnitude identity:

Then we use the distributive property to break down the expression even more:

And finally, using the commutative property:

This is as simple as we can go when trying to break down the left hand side of equation 26, but the great thing about this is that if we use the magnitude identity once more, but backwards and we will obtain:

Which proves that equation 26 holds true.

Example 7

Suppose vector is orthogonal to vectors and . Show that u is also orthogonal to .To solve this particular problem we need to realize that if vector is orthogonal to vectors and , then the next conditions hold true: and . And so, for to be orthogonal to , then we need to prove that . So let us compute that:

As you can see above, due to the distributive property, we can distribute the dot inner product of with and separately. Since we know that both of those product are zero (is the initial condition of this question) then, the result is that the dot product is also equal to zero, making orthogonal to .

To finalize this lesson we would like to recommend you to visit the next wonderful notes on the inner product, length and orthogonality and this handout on the same topic containing some extra example problems.

This is it for our lesson of today, see you in the next one!

Let vectors and be:

Then the inner product of the two vectors will be:

Let and be vectors in , and let be a scalar. Then,

1)

2)

3)

4) , and only if

Suppose . Then the length (or norm) of a vector is

. Then the length (or norm) of a vector is

Suppose dist is the distance between the vectors and . To find the distance between the two vectors, we calculate

dist

If two vectors and are orthogonal to each other, then it must be true that

Then the inner product of the two vectors will be:

Let and be vectors in , and let be a scalar. Then,

1)

2)

3)

4) , and only if

Suppose

. Then the length (or norm) of a vector is

. Then the length (or norm) of a vector isSuppose dist is the distance between the vectors and . To find the distance between the two vectors, we calculate

If two vectors and are orthogonal to each other, then it must be true that

and

and  , compute:

, compute: and

and  , compute:

, compute:

and

and  .

.